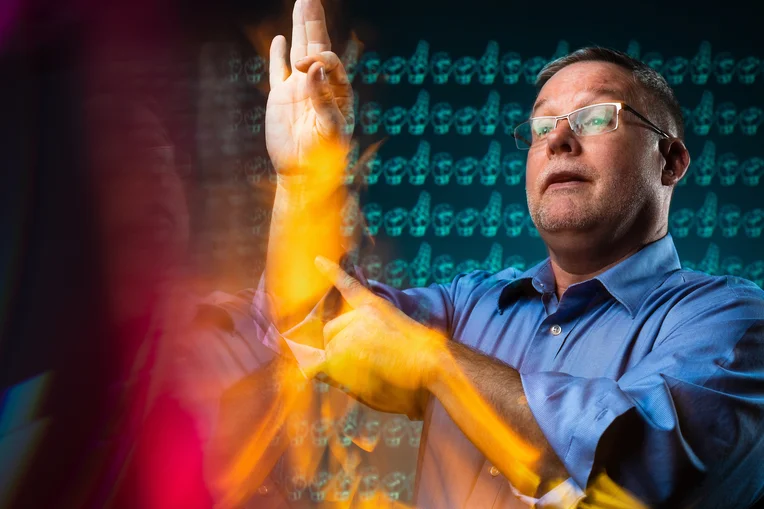

Quest Magazine Dr. Basil Kessler

"My professional journey began when I was in the high school seminary."

Basil Kessler fell in love with the Deaf Community, who he now serves through sign language education courses, amongst others, through the Counselor Education Department at ESU.

“Unbeknownst to me, my professional journey began when I was in the high school seminary,” said Basil Kessler, assistant professor in the Department of Counselor Education at Emporia State University.

“I decided to continue onto college seminary because I had no idea really what I wanted to do. When I made that decision, I was unaware that the order to which I was affiliated with was the first religious group to work with Deaf Catholics,” said Kessler. “I was approached by a guy who was an older seminarian. He had already taken vows, and he said ‘I hear you’re interested in working with deaf people?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I’m fascinated by it,’ because by this point I had taken a few workshops in high school where one of the priests was teaching some signs and I had thought, ‘I really like this!’. But I told him I didn’t know how to sign.”

The older seminarian gave Kessler a book on sign language. Kessler began studying the book with a friend in the evenings and became further intrigued with the language.

“I literally memorized all the signs in this book … I memorized all the signs in the fall semester and started teaching a religion class at the School for the Deaf in Wisconsin,” he said. “I got hooked, and a certain man said ‘Basil, you have a gift. I think it would be really worth your while to look into Deaf education.’ That’s what sparked it all.”

Kessler went on to graduate from college with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy, and he moved back to his hometown of Wichita, Kansas. His calling was still clear at this point, and he intended to continue to pursue Deaf education.

“I became enamored with the people and their language. Upon graduation I began working in Wichita for a United Way funded program, Deaf and Hard of Hearing Counseling Services, which, come to find out, was the first social service agency of its’ kind in the country, having been established in 1959.”

After six months in this position, Kessler decided he wanted to something in the mental health realm, so he enrolled in a master’s degree at Wichita State University.

“I knew I wanted to do more than what I was doing at the time. I wanted to be a psychotherapist for the Deaf, but I needed credentials of some sort, so where could I find those credentials? I had to find them in higher education and through attending workshops and trainings and getting supervision in all of those things,” explained Kessler. “Interestingly enough, this was before licensure was even a possibility in the counseling field.”

“Fortunately classes were in the evening. I worked as a case manager, became a certified interpreter and found myself immersed within the lives of Deaf people and their families. It’s hard to explain what an honor that was for me. I developed close friendships with many Deaf folks from Wichita, their spouses and children. I found myself interpreting for parent-teacher conferences, physicals, chiropractic appointments, meetings with rehabilitation and social security professionals and even the birth of a child. It was humbling to realize just how much I was involved in very personal matters -- a responsibility that was and remains quite sacrosanct.”

Shortly after completing his master’s degree, Kessler was hired as a consultant by DCF as a reintegration therapist for families with Deaf members.

“In 1988, Dr. Lloyd Stone, Chair of the ESU Counselor Education program, called me out of the blue and said, ‘Basil, your name has been given to me as a possible sign language teacher. Would you be interested in doing so?’ So I told him I needed to talk to my wife,” said Kessler. “As it turns out, I elected to pursue a doctoral degree because I believed I needed stronger clinical skills to provide ethical counseling and psychotherapy services to Deaf and hearing clients.”

Kessler entered his doctoral program at Kansas State University and with encouragement from family and colleagues, he began as a lecturer for ESU while working on his doctorate. Kessler taught at the undergraduate level and also advised at the Student Advising Center.

“It proved to be a wonderful opportunity to be able to apply what I was learning at the doctoral level in the classes I taught and the advising I was doing,” he said.

While serving as a student and junior faculty member, Kessler and his wife, Annette, had three children.

“My biggest obstacle was probably finding a balance between taking care of my family -- being a spouse and a father -- while trying to build a professional identity, because that professional identity takes a tremendous amount of effort and time and money,” said Kessler. “I was fortunate enough that my wife was willing to put up with me going back to graduate school. Then when I finished, she went back to graduate school. We had to have that trade-off.”

Kessler noted that it became quite evident he needed to establish himself professionally, which led him to become involved in professional organizations and social service groups. Those experiences further helped him use the skills learned in school and helped him refine his networking skills.

“One thing I can’t emphasize enough and which I try to share with my students is the importance of positioning yourself to be engaged in a variety of opportunities that will help define you as a professional in your field of study. Positioning allows you to develop the network of professionals upon whom you may rely for the remainder of your careers.”

As Kessler refined his skills and became involved in state and national-level policies impacting the Deaf community, the stint with ESU did not last long thanks to some other opportunities that Kessler said “yes” to.

“While at ESU, I was appointed to the Kansas Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing as the interpreter representative. Two years later, I was appointed as the mental health representative. I continued in that position as I completed my doctoral degree,” said Kessler. “Serendipitously, I had the fortune of being asked to serve as the liaison between the Kansas State School for the Deaf and the Kansas State Department of Education which I did for six years. I continued to serve on the Commission and was named an ex officio member when the State Director of Special Education unexpectedly passed away. I was humbled to attempt to fill her shoes.”

Prior to returning to ESU in 2015, Kessler served for twelve years as the Executive Director of the Alternative Finance Program in Kansas. This grant program was a Department of Education grant to the University of Kansas. Kessler used his experiences in the not-for-profit world and his understanding of disability, public policy and interpersonal communication to operate that 12 million dollar program. It was soon after he left that position that ESU asked him to serve as an adjunct professor for two semesters. He was then asked to work under a 9-month contract with the Counselor Education Department. He learned of faculty vacancies in that department and successfully applied for an Assistant Professor position in the Clinical Counseling program.

Through all of the schooling and position changes, Kessler was challenged, as are many going through graduate school as establishing themselves professionally. The work paid off, and so did the balancing act; the impact of Kessler’s career with the Deaf community was not limited to Kessler himself.

“I attempt to bring many of my professional experiences into the classroom and help students find their own professional journey. The professionals I have known and worked with for the past 40 years can now be their peers and professional resources. My life experiences inform my work as professional counselor and counselor educator,” said Kessler. “My affiliation with the Deaf community makes me really take a look at my own assumptions about life -- assumptions about what is a good life, what is a wholesome life, what is a fulfilling life. It’s taught me the difference between a problem and an inconvenience, and I think that’s something I’ve been able to share with my children. Many of the things that we see as a problem is actually just an inconvenience at best.”